A woman walks into your office and it's clear she has Spleen qi deficiency. She's overweight, tired, and a busy executive who travels frequently. You explain to her that she is going to need to eat more millet, less dairy, little-to-no raw fruits and vegetables, and you give her an herbal formula. You don't notice her eyes glazing over, and you realize weeks later that she never returned.

What's missing here? It's not your OM education — regardless of which school you went to, you graduated with a solid understanding of acupuncture and possibly also herbs. You learned a fantastically complex system of health and healing that has served people for thousands of years. You make a difference in people's lives and health every day. There's just one problem. The modern American patient is very different than the traditional Chinese patient, and not realizing those differences is resulting in you being a less effective practitioner.

The perfect example is the Chinese description of diabetes, "wasting-and-thirsting" disease. At some point we probably realized that this was referring to Type 1 diabetes, and not the epidemic of diabetes we now have with Type 2. The problem is, while we know that sugar is problematic nowadays, this wasn't true in traditional Asia, so we're left to figure out on our own what to do. What's a "safe" amount of sugar? Is brown, unrefined sugar better? (No.) What about agave nectar? (Definitely not.) We often don't realize that refined carbohydrates break down into glucose within an hour, acting the same way as regular sugar, or that fructose is hugely problematic (or even that fructose is half of the sugar molecule). We assume whole grains are healthy, not realizing that people whose systems are "broken" often can't tolerate the carb overload of whole grains. We make some dietary changes that often don't make much difference or that the person can't relate to (remember the busy executive from the first paragraph?) and, because we don't know enough about modern nutrition, ever get a chance to reverse this person's insulin resistance or diabetes.

What's missing is a bridge between traditional Chinese nutrition and what the modern patient is eating (or not eating) now. Because there are some gargantuan differences and knowing them and adjusting for them will make your treatments more beneficial.

What's missing is a bridge between traditional Chinese nutrition and what the modern patient is eating (or not eating) now. Because there are some gargantuan differences and knowing them and adjusting for them will make your treatments more beneficial.

Let's take the second example of the vegetarian. The traditional Chinese person may have had periods of time where they didn't eat meat, but it wasn't by choice and they ate it when they had it. They also ate the entire animal — the organs, made soup from the bones, ate the chicken feet, etc. because all of those parts have nutrition that is unmatched. Only in more modern times, where we're not driven by the specter of starvation, do we deliberately remove a food group from our diets. Unfortunately, this leads to nutritional deficiencies like B12 (available only in animal products) which could be the root cause of this person's fatigue. If you don't know enough about these deficiencies to make this recommendation, all the herbs in the world won't help his exhaustion.

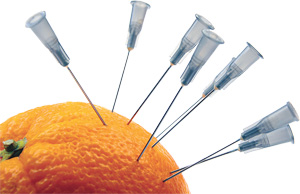

Traditional Chinese also didn't eat low fat, as the fat provided not only calories but nutrients as well. In fact, it is only in the last 30 years that we have gone completely against a millennia of humans and traditional eating, and in our demonization of fats (have we lost our minds?) jump-started the diabetes epidemic in this country. The Chinese also didn't do crazy things like avoid eggs (surely you know the Chinese saying: "You eat as many eggs as you can afford for a smart baby"?). In using the whole animal and making bone broths, they provided for themselves a plethora of minerals and nutrients that we are sadly lacking (traditional cultures have been shown to have four times more calcium in their diets than we do, as an example). They lacto-fermented foods, providing natural probiotics, and they ate seasonally. We, of course, do not, eating oranges in June, and strawberries in December.

The United States eats more sugar than any other place on the planet, and living in this little slice of time, we seem to think it's relatively normal. We know it's "bad", but we think "moderation" might be OK. But the traditional Chinese didn't have to deal with an overload of sugar and it's connected problems (although they are now) and we have no idea how off the scale we are (no pun intended). About 300 years ago, we ate four pounds of sugar a year, and now the average American eats upwards of 150 pounds. Even if your patient decided on "moderation" and cut it in half to 75 pounds a year… it's like cigarettes or alcohol: how much is safe? We don't really know. And the problem is, it's playing into symptoms you spend valuable time chasing around, never really catching: insomnia, fatigue, gas and bloating, headaches, high cholesterol, joint pain, anxiety, cancer. And the list goes on from there.

It's also vital to know how wildly adulterated our food is nowadays, because that makes a difference in it's nutritional content, as well as to how it interacts in our bodies. We don't seem to realize how "messed with" our food is: processed liquid oils that raise your Omega-6's and increase your inflammation, the constant marketing that soy is healthy (it's the second largest crop we have — do you think that might have something to do with it?), again, the demonization of fats that have led to low-fat foods, the over-farming that has depleted our soils and therefore our produce, conventional factory farming that is not just cruel, but also changes the nutritional composition of the meat, and the addition of hormones and antibiotics to those animals that end up in our bodies.

With the health of Americans deteriorating, does it really work for you to get your nutritional "advice" and information from the same places as your patients? The news, magazines, advertisements… where they talk about one "miracle" berry for weight loss, cancer reduction, energy, sleep? Where books spouting veganism don't ever mention the nutritional deficiencies that occur? Where some biased research study mentions that six cups of coffee can prevent this specific type of cancer? Or when their doctor, who's not a nutritionist, tells them to take Vitamin E. Your patient goes to the drug store and buys alpha-tocopherol or ascorbic acid, or beta-carotene, not realizing the different between that isolated synthetic chemical and real food. And that difference is graphic: synthetic vitamin antioxidants have been shown to increase rates of cancer, increase heart disease, increase infertility, and more.

Because there are so many sources now for information, we have to remember our training and be able to put it in the framework of modern society. Just because we learned that congee is good for digestion in a classic text from 1,000 years ago doesn't mean we should be recommending it to our overweight, Spleen qi deficient patients who are insulin resistant. And using blood deficiency herbs for anemia worked when people were eating things like liver — relying on herbs to turn around anemia when people are eating poorly is risky and slow going.

Everything is taken so out of context, and as OM practitioners, we're trying to bridge this gap between the traditional medicine we learned, along with the traditional nutrition we learned, and squeeze it into this modern society framework, and the lack of context doesn't help. But I would go so far as to say this: I would consider it our ethical obligation to learn about nutrition, if only because your patients will come to you and ask you what they should take and eat to be healthy, and if you think it's a multi-vitamin and being vegan, you are doing actual harm to your patients.

Nutrition was one of the pillars of Chinese medicine but many of us are "forcing" our traditional education into a modern framework, and it's not working well. You might consider starting to build a bridge and begin to learn more about what we could eat to be healthy, what modern foods "look" healthy but aren't (soy, fruit juice, agave nectar, and those "healthy" butter-like spreads made from unhealthy oils, for example), and distinguishing between all the marketing of synthetic vitamins, and what an actual "food concentrate" gives a patient.

I make this last point because label-reading is something that most people don't understand. You can tell a vitamin is synthetic because the label often puts the vitamin isolate in parentheses (Vitamin C (as ascorbic acid), for example), and then gives round number amounts like 400% and 1000 mg. You don't get exact amounts like that in foods and who needs a gram of a synthetic vitamin anyway?

So consider learning more about the actual mechanism of diabetes, which vitamins are in which foods, what modern deficiencies are common (zinc, stomach HCl, magnesium, vitamin D, vitamin B's, amongst others) and how to recognize them. Learn what traditional cultures ate to gain all their vitamins and minerals and begin to realize how this meshes with your OM background. Consider taking a seminar outside of your OM field in nutrition. The difference it will make for you will be remarkable, and the difference it'll make for your patients will be unimaginable.

- Coffee Consumption and Prostate Cancer Risk and Progression in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst (2011) 103(19): 1481

Click here for previous articles by Marlene Merritt, DOM, LAc, ACN.